|

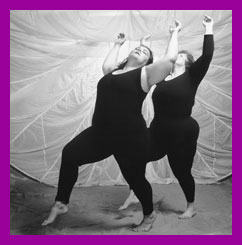

By Marina WolfPhotos by John HoadleyFrom Radiance Winter 2001.

I recently watched these large dancers in a one-hour segment of Hot Topics, a documentary show on Canadian cable channel WTN, which originally aired in January of 1999. My tiny TV screen could not diminish the spirit or energy of Big Dance. Big Dance is both a troupe and the class that feeds it, led by choreographer Lynda Raino at her dance school in Victoria, British Columbia, Canada. As she explained on the show, Raino, an esteemed modern dancer in North American circles, got the idea for Big Dance after collaborating with a large woman on an art project. The woman said that she’d take a dance class if Raino offered one specifically for large women. Raino jumped on the idea immediately. But the actuality of large dance came as a surprise to her.

Dance teachers will testify that every body, no matter what size, has its own limitations. Part of learning dance is about exploring boundaries and making the most of what you have, something with which Raino is intimately familiar. A few years ago Raino suffered a badly herniated disk and required both surgery and rehabilitation. She was told that she might never walk again, let alone dance. But Raino emerged from this situation even more determined to dance, and she set out to learn what she could and couldn’t do. “My dancing has changed incredibly in the past year, since the surgery,” she says. “I used to love spinning, pirouettes, jumps. But the control and high extensions of my legs are gone. So now I must express myself another way.” In class Raino offers that same adaptability to her students. Bends may be modified or leaps reduced: really, anything can be changed as long as the feel of the movement is preserved.

Usually dance classes are almost entirely about technique; indeed, that had been Raino’s original intent. But she soon came to realize that for these dance students, the art form of dance was inseparable from the spiritual and psychological issues that the movements stirred up. “I wasn’t sure how technical I could be with them. It became clear to me very soon that the technique of dance was not the priority. What was required was to free up the dancer’s spirit in them. Big Dance is hard work. I spend more time on Big Dance than on any other class in my school. They’ve had more issues to overcome: issues of self-esteem and where they belong and their acceptance in this school.” Considering the collective experience of large women in dance institutions, these feelings are understandable. Entire generations of fat girls have suffered through classes, and many have been screened out of dance entirely, thanks to family, teachers, or just the harsh and narrow expectations of the dance world. Hot Topics includes extensive interviews with members of Big Dance, the youngest of whom, Jennifer, recalls how much she loved dance as a girl. “When I was younger, I was into tap, ballet, jazz. When I was eleven or twelve I was in a jazz class, and that’s when I became really aware of the differences in body types and stereotypes and the way society makes some people feel about their bodies. It was just really uncomfortable for me. I was self-conscious and really aware that I was not like the other girls. We had to wear short little costumes, very tight and revealing, and so I ended up quitting, because I didn’t like it there anymore.” Jude, another Big Dance member, recalls watching variety shows, loving the dancers, and wanting to be like Cher. When she took aerobics classes, she would pretend that they were real dance classes. But when she came to Big Dance, she had to start moving almost from scratch. “I didn’t have a lot of confidence in my ability to do things in my body,” she confesses. “I certainly had confidence in my abilities intellectually and in the work that I do in the world. But I felt quite insecure about moving and being in my body, and I still struggle with this sometimes. I hear the music in my head before I feel it in my body.”

Through Big Dance, Trudy has found her body and now is dancing toward a greater acceptance of it. “Part of [my focus] is the body that I’m in and accepting and loving that body and being able to become free in the body that God has given to me.” The dancers are uniformly grateful for the therapeutic possibilities offered by dancing with other large women. Says Terryl, a plain-spoken Ph.D. student, “The first year I was in Big Dance, it saved my soul. Any creative endeavor, when you put your heart and soul into it, is bound to be therapeutic”.

Possibly their greatest triumph was an appearance at the North and South American World Dance Alliance, a conference about dance in North and South America that took place in Vancouver, British Columbia, in 1997. Upon reviewing a video of Big Dance’s choreography, conference organizer Judith Garay saw the value of the group’s work and extended an invitation to them. “I think that people do have very specific expectations of dance, and that’s not the best thing for the art form,” says Garay, who heads the dance department at Simon Frasier University in British Columbia. “In this culture, we’ve taken dance and put it in very specialized venues and out of the lives of the people. In many other cultures, dance is part of people’s lives. Everybody dances. But here you have to be someone who’s trained from age three. I actually believe that everyone can dance. Not everyone wants to or is able to be a professional dancer, but everyone can dance.”

Exploring how to present themselves to the outside world is also part of the dancers’ path. Differences in personal comfort levels with the director’s artistic vision make this act of self-definition occasionally problematic. One of Raino’s favorite pieces, for example, is a rendition of the balletic hippopotamuses from Fantasia. Several of the dancers have expressed uneasiness about keeping that piece in the company’s repertoire. Trudy says, “At first I was hypersensitive to being laughed at, and I thought Lynda wasn’t being sensitive to that.” For her part, Raino believes the piece to have its own therapeutic value. “I think that the best medicine for any of our doubts is laughter,” she says. “Humor is the most wonderful way to plow right through all kinds of stereotypes, and also your own pain. For [these dancers] to put on pink tutus and do a parody of themselves as hippopotamuses tells me that they’re in really good mental health, that they are ready to laugh at and accept themselves, and I’m so proud of them for that.” Other numbers have emerged organically out of members’ personal experiences. For example, one dancer shared with the group the story of a social evening she’d enjoyed that had ended in a skinny-dipping session. This evolved into the dance troupe’s own creation of a buoyant ballet that they enact onstage in a dreamy, mysterious dance of self-affirmation. And this piece forms just one of many documented in the hour-long footage of Big Dance that proves their work to be uniquely instructive and entertaining—as well as revolutionary—for dancers and nondancers alike. ©

Individual copies of the Big Dance video can be ordered through Kinetic Video: $39.95 for at-home use, $179.95 for institutional or public viewing. Their web site is www.kineticvideo.com, or call 800-466-7631 (United States) or 800-263-6910 (Canada). After two-and-one-half years of picking up dance classes wherever she could, MARINA WOLF is enrolling in the dance certificate program at Santa Rosa Junior College in Northern California. She wants to get more fat women in the dance studios and on the dance floors of the world. When she isn’t dancing, Marina is cooking, eating, or writing about cooking and eating. You can contact her at fullsun@sonic.net, especially if you have leads on custom-made dancewear (leotards, jazz pants, crop tops, and so on) in size 28.

|

|

Radiance. |

||

|

This site maintained by Cory Computer Systems. |

||

n a world

designed by large women, things would surely

be different. Airline seats would be at least ten inches wider. Chairs

would be larger and sturdier. Bras would be better made, better looking,

and cheaper. And instead of only willowy-thin dancers, the stages of the

world would be graced by more women the size of those in Big Dance.

n a world

designed by large women, things would surely

be different. Airline seats would be at least ten inches wider. Chairs

would be larger and sturdier. Bras would be better made, better looking,

and cheaper. And instead of only willowy-thin dancers, the stages of the

world would be graced by more women the size of those in Big Dance. “I had no game plan, which was a little bit frightening. I had no idea

what it would be like to try to teach dance to someone with a 300- or

350-pound body,” says Raino. “I realized that there were going to be

physical limitations. I realized I was going to have to take care of

backs, knees, ankles in ways that were obviously safety issues. But what I

hadn’t planned for was to ask the women to bend forward, and they

couldn’t. There was a large breast or a stomach in the way. I realized

right away I was going to have to ad-lib here and be very creative. It was

wonderful. . . .I’ve never been so unprepared and so open to have a

process evolve with the people. Usually the teacher is in charge, but we

really evolved this dance format together.”

“I had no game plan, which was a little bit frightening. I had no idea

what it would be like to try to teach dance to someone with a 300- or

350-pound body,” says Raino. “I realized that there were going to be

physical limitations. I realized I was going to have to take care of

backs, knees, ankles in ways that were obviously safety issues. But what I

hadn’t planned for was to ask the women to bend forward, and they

couldn’t. There was a large breast or a stomach in the way. I realized

right away I was going to have to ad-lib here and be very creative. It was

wonderful. . . .I’ve never been so unprepared and so open to have a

process evolve with the people. Usually the teacher is in charge, but we

really evolved this dance format together.”

dapting does not mean that the dancers are taking it easy. Raino says

that at first she was nervous about the possibility of physical overload.

But as the class worked and grew together, everyone learned what was

possible. “The more they could take, the more I gave them. The more I

gave them, the more they wanted,” says Raino. “I want from them as

much as I want from any dance group. I want them to dance their best. I

want them to never stay where they are, but to continue to improve. I have

demanded that they take more classes, that they be more physically fit,

and they continue studying the craft of dance.”

dapting does not mean that the dancers are taking it easy. Raino says

that at first she was nervous about the possibility of physical overload.

But as the class worked and grew together, everyone learned what was

possible. “The more they could take, the more I gave them. The more I

gave them, the more they wanted,” says Raino. “I want from them as

much as I want from any dance group. I want them to dance their best. I

want them to never stay where they are, but to continue to improve. I have

demanded that they take more classes, that they be more physically fit,

and they continue studying the craft of dance.” Such dissociation can be severe, as Trudy, another dancer, relates. “I

felt totally disassociated from my body in every sense, as if I didn’t

exist below my neck or above my ankles. I’d always have nice toenail

polish and pretty shoes, but ugly clothes and then nice makeup and hair.

This huge zone was totally missing for me. My understanding is that this

is not uncommon in large women. I didn’t look at myself. I never had a

full-length mirror. I would only look at my face and feet, and try to wear

something that covered up everything else.”

Such dissociation can be severe, as Trudy, another dancer, relates. “I

felt totally disassociated from my body in every sense, as if I didn’t

exist below my neck or above my ankles. I’d always have nice toenail

polish and pretty shoes, but ugly clothes and then nice makeup and hair.

This huge zone was totally missing for me. My understanding is that this

is not uncommon in large women. I didn’t look at myself. I never had a

full-length mirror. I would only look at my face and feet, and try to wear

something that covered up everything else.” As for the dancers, they

express a typical range of responses to performing, from hyperactive

excitement to extreme panic and nausea. But as a group, they seem to feel

that performing is important. “It means a lot to me to be able to get

out in front of people and have them accept what we do as meaningful

within society,” says Terryl. “What Lynda Raino has done for us has

had such an impact on our lives. I would like that to be available for a

lot more people.”

As for the dancers, they

express a typical range of responses to performing, from hyperactive

excitement to extreme panic and nausea. But as a group, they seem to feel

that performing is important. “It means a lot to me to be able to get

out in front of people and have them accept what we do as meaningful

within society,” says Terryl. “What Lynda Raino has done for us has

had such an impact on our lives. I would like that to be available for a

lot more people.”