|

|

|

QUOTES

FROM PEOPLE

WHO |

From Radiance Winter 2001.

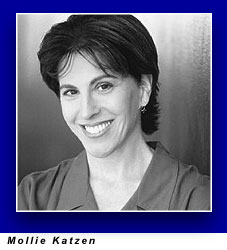

![]() donít want to eat genetically modified foods,

and I donít want people whom I care about to eat them, either. Iím

basing that on my feelings about how genetically modified foods are being

presented to the public: We donít know that itís harmful, so therefore

itís okay. I just donít find that very scientific, and it seems very

self-serving as well. Anytime I see something that greatly increases the

profit of very powerful companies, with big public relations budgets to

convince people of it, it makes me suspicious. It should be proven to be

safe, but instead theyíre saying that itís not proven to be harmful. I

would rather they do some more tests on this stuff. Take those Roundup

packaged soybeans. I donít really want to eat soybeans that have

pesticide already inside them. Itís a little disconcerting!

donít want to eat genetically modified foods,

and I donít want people whom I care about to eat them, either. Iím

basing that on my feelings about how genetically modified foods are being

presented to the public: We donít know that itís harmful, so therefore

itís okay. I just donít find that very scientific, and it seems very

self-serving as well. Anytime I see something that greatly increases the

profit of very powerful companies, with big public relations budgets to

convince people of it, it makes me suspicious. It should be proven to be

safe, but instead theyíre saying that itís not proven to be harmful. I

would rather they do some more tests on this stuff. Take those Roundup

packaged soybeans. I donít really want to eat soybeans that have

pesticide already inside them. Itís a little disconcerting!

Iím not saying that technology is all bad, because I certainly think it would be fantastic if technology can be used to increase the nutritional profile of anything, in a good way. But I donít believe thatís the purpose here: the purpose here is to increase profitability.

I care more about how clean my food is than almost anything else. Lots of times, Iíll be out to dinner with people, and people will get all bent out of shape about whether Iím eating meat or theyíre eating meat, because I write vegetarian cookbooks. But thatís so far from my primary concern. Iíd rather eat a piece of clean beef than a piece of broccoli thatís laced with pesticides. Clean food, clean water, and clean air: I think that those are the biggest keys to health.

óMollie Katzen, author of a number of cookbooks,

including

The New Moosewood Cookbook,

Vegetable Heaven,

and The New Enchanted Broccoli Forest Cookbook

hen weíre talking about genetically modified foods

and how they will affect us, we have to distinguish between people who buy

things in boxesówhat I call chemical cookingóand those of us who use

fresh, natural ingredients. Those of us who buy fresh are terribly

concerned. We just donít know the effects. Say you eat chicken twice a

week. If you eat a tomato with a chicken gene, youíre eating that

chicken gene many more times a week. We donít know what thatís going

to do throughout forty years. How dare these people do that to my food? I

understand that all plants are hybrids and crossbred. We all have to deal

with pesticides and fillers and strange things being fed to animals. But

this, I think itís beyond the pale.

hen weíre talking about genetically modified foods

and how they will affect us, we have to distinguish between people who buy

things in boxesówhat I call chemical cookingóand those of us who use

fresh, natural ingredients. Those of us who buy fresh are terribly

concerned. We just donít know the effects. Say you eat chicken twice a

week. If you eat a tomato with a chicken gene, youíre eating that

chicken gene many more times a week. We donít know what thatís going

to do throughout forty years. How dare these people do that to my food? I

understand that all plants are hybrids and crossbred. We all have to deal

with pesticides and fillers and strange things being fed to animals. But

this, I think itís beyond the pale.

Iím resolved to grow as much as I possibly can. We happen to have a great farmerís market. The Dutch farmers around here take great pride in their produce, and the amount of strange things that they put on the soil is minimal. If you really seek out the best seasonal ingredients and you buy things at their prime, thatís when food is least expensive. And in the kitchen you have far less to do to make your food taste really good.

As for the people who do chemical cooking, all I can say is, Stop it. The difference between homemade whipped cream, for example, and Cool Whip is enormous, what with all the preservatives and hydrogenated oils they put in it. You donít know whatís in those things, you canít even pronounce the ingredients, and youíre spending so much more for somebody to package and distribute it. Thereís no reason to buy that stuff. Sometimes I make my own mayonnaise, sometimes I buy it. But the taste is never there. And my overriding choice is taste.

óJulee Rosso-Miller, coauthor of the Silver Palate cookbooks

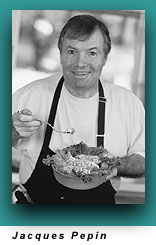

![]() ím neither for nor against genetically modified

foods. It is easy to reject the whole thing in one block. I just want to

be able to evaluate each product on its own merits. If you tell me, a

chef, that you will make me a tomato that really tastes like a tomato,

that has all the flavor and will last for a week, that doesnít have to

be sprayed with insecticides or pesticides, why not? I do not see anything

wrong with it. Things have always been modified in one way or another.

Eventually, people picked up wild grass, planted it, and crossbred

itóand now we have wheat. Fifty years ago, you had to string the beans

or they were inedible. But now there is no more string in the beans. The

meat is much leaner and apples are different. Crossbreeding is not exactly

GM, but Iím talking about manipulation and modification, and humans have

been doing that forever.

ím neither for nor against genetically modified

foods. It is easy to reject the whole thing in one block. I just want to

be able to evaluate each product on its own merits. If you tell me, a

chef, that you will make me a tomato that really tastes like a tomato,

that has all the flavor and will last for a week, that doesnít have to

be sprayed with insecticides or pesticides, why not? I do not see anything

wrong with it. Things have always been modified in one way or another.

Eventually, people picked up wild grass, planted it, and crossbred

itóand now we have wheat. Fifty years ago, you had to string the beans

or they were inedible. But now there is no more string in the beans. The

meat is much leaner and apples are different. Crossbreeding is not exactly

GM, but Iím talking about manipulation and modification, and humans have

been doing that forever.

When I was a child, when we baked a chicken we had to baste it a lot or it was rubber. Now it is impossible to have dry chicken. Itís true that chicken is less firm and has less taste. To a certain extent, we are what we are, this is what the palate is like, what we have been raised with. Our standards are different from generation to generation. I raise chickens with a friend, and when we give that chicken to people, even though they think that they want food from thirty years ago, they say, Oh, that is kind of strong.

I think Americans will be fine with genetically modified foods. If we can do good with it, then we can do great things. Itís like nuclear energy: we cannot go back, itís here. This is not a license to modify things without people knowing about it. We have to study and gather more knowledge about it. The biggest issue to start with is the industryís secrecy. They should advertise it and label it for what it is. We have to be open.

óJacques Pepin, television chef, and author of a

number of cookbooks, including Jacques Pepinís Table, The Complete

Todayís Gourmet,

and Julia and Jacques Cooking at Home

ood food begins in good earthóin the ďheartĒ of

that loving, natural interaction between farmer and environment. Thatís

what would be lost in the genetic engineering of our food. The laboratory

test-tube approach to creating food makes each of us question our

commitment to the fragile web of soil, sunlight, and water. Our political

votes and our votes as consumers in the marketplace are critical to the

future of our precious land, which has supported us for generation upon

generation.

ood food begins in good earthóin the ďheartĒ of

that loving, natural interaction between farmer and environment. Thatís

what would be lost in the genetic engineering of our food. The laboratory

test-tube approach to creating food makes each of us question our

commitment to the fragile web of soil, sunlight, and water. Our political

votes and our votes as consumers in the marketplace are critical to the

future of our precious land, which has supported us for generation upon

generation.

óLinda Tanner, food writer

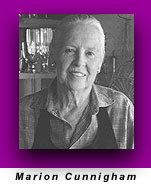

![]() have to say that Iím averse to the idea. This

isnít just a question of, say, developing a new fruit tree. Thereís an

intrinsic danger in the fact that we donít know any of the effects that

it might have. Iím not sure why theyíre doing it in the first place.

have to say that Iím averse to the idea. This

isnít just a question of, say, developing a new fruit tree. Thereís an

intrinsic danger in the fact that we donít know any of the effects that

it might have. Iím not sure why theyíre doing it in the first place.

My little personal experience was with a tomato that had a bit of shark gene in it. That tomatoówe all tasted it at a meeting of food professionalsóit was yucky. Not much flavor, not much juice. Oh, God, when I think of what weíve learned to live with: shipping, packing, and preserving. In order to ship them, tomatoes are not as vulnerable on the vine as they used to beóand theyíre not as juicy. Itís like a mummy. If people could eat some of the food I ate when I was growing up, theyíd know. Todayís available meat, they take all the fat off, so there is no flavor.

And the fruit! I went along the counter of Safeway the other day, and I picked up every stone fruit. Hard as rocks, no flavor. It was absolutely horrible. And people donít know, they donít even know that thereís better fruit than that.

I make it sound like doomsday, but I really do feel that the humanness of our lives is slipping away. We have to come back to cooking at home. Itís about more than the food. It acts as a metaphor to bring you to the table, to learn to act civilized with others. If we donít have daily interaction with people, we very quickly slip into not recognizing the needs of others.

I donít know how to alert the country about genetically modified foods. People donít read food articles and they donít read labels. I donít think anythingís going to stop this. I donít see how, unless the effects of these vegetables are such that they make people sick. Theyíre going to have to poison some people before people pay attention. Oh, dear, I wish I werenít so pessimistic.

óMarion Cunningham, chef, and author of a number of

cookbooks, including The Breakfast Book, The Supper Book, Cooking with

Children,

and The Fannie Farmer Cookbook.

lthough I understand the science behind genetically

altered food, I am concerned about our ability to utilize this science for

the benefit of human beings and the world we live in. In the past twenty

years, I have witnessed the commercialization of our entire value system

to the point where the driving force behind almost all decisions is money.

Until I see human beings begin to value what really matters in life, I do

not trust us to make good decisions about this new science.

lthough I understand the science behind genetically

altered food, I am concerned about our ability to utilize this science for

the benefit of human beings and the world we live in. In the past twenty

years, I have witnessed the commercialization of our entire value system

to the point where the driving force behind almost all decisions is money.

Until I see human beings begin to value what really matters in life, I do

not trust us to make good decisions about this new science.

óJoanne Ikeda, M.A., R.D., nutritionist, University of California, Berkeley, and codirector of Weight and Health

![]() his is such a big topic. You need to be something of an

expert to talk about it intelligently, but I certainly have a visceral

response to it. I think genetically engineered food will contribute to

more of a nonthinking relationship to food and how itís grown and where

it comes from. Weíre already pretty bad on that score. Few people know

what real food tastes like, what a real strawberry tastes like, or a ripe

peach. I donít see that genetically modified types of food are going to

do anything to inform people about the real tastes and possibilities of

food.

his is such a big topic. You need to be something of an

expert to talk about it intelligently, but I certainly have a visceral

response to it. I think genetically engineered food will contribute to

more of a nonthinking relationship to food and how itís grown and where

it comes from. Weíre already pretty bad on that score. Few people know

what real food tastes like, what a real strawberry tastes like, or a ripe

peach. I donít see that genetically modified types of food are going to

do anything to inform people about the real tastes and possibilities of

food.

When I give a class now, Iím committed to using locally grown produce. I donít want to go to the supermarket and just buy whateverís there. I want people, in my classes at any rate, to see what incredible, vibrant possibilities exist in their own communities and in their own backyards and that these are worth protecting. I always know that people will like what I cook, because the flavor is going to be there, without adding a lot of sugar or salt or fat.

Most communities have farmerís markets now, where it really isnít that much more expensive to shop. Itís always easier to go to the supermarket and pick up something there, but at the farmerís market you interact with people and have a good time and the end result is so much nicer. Youíll be sitting down to the table with good local food, which is a very different experience from sitting down to nothing but a lot of unanswered questions about your dinner.

óDeborah Madison, chef, and author of a number of cookbooks, including Greens Cookbook, This Canít Be Tofu, and The Savory Way

From the foreword to On Good Land: The Autobiography of an Urban Farm, by Michael Ableman (Chronicle Books)

e have] been speakers and panelists at the same

symposiums ó Michael representing the farmer, me representing the

restaurateur, both of us stressing the connection between the field and

the plate. . . . I see now how his philosophy about good food and

responsible agriculture took shape in the daily struggle to keep one small

farm alive and flourishing.

e have] been speakers and panelists at the same

symposiums ó Michael representing the farmer, me representing the

restaurateur, both of us stressing the connection between the field and

the plate. . . . I see now how his philosophy about good food and

responsible agriculture took shape in the daily struggle to keep one small

farm alive and flourishing.

[The farm is] set right in the middle of generic suburban sprawlósurrounded, but not swallowed up, by the banal urbanization that has destroyed so much of California farmland. [This farmís] continued existence demonstrates that there may yet be hope, even in the midst of strip malls and fast food joints: hope for slow food and all that ought to implyógrown organically by people who live and work nearby; food you can buy directly from the grower; food that will be prepared, served, and shared by families and friends.

. . . Michael knows firsthand both the environmental wisdom and the cultural benefits of small scale, diversified agriculture. . . . This book . . . offers the humble reminder that good food starts in fields and orchards well tended. This is knowledge that we ignore at our peril, for without good farming there can be no good food; and without good food there can be no good life.

óAlice Waters, chef, founder of the Chez Panisse restaurant in Berkeley, California, and author of a number of cookbooks, including Chez Panisse Menu Cookbook and Chez Panisse Vegetables

|

Radiance. |

||

|

This site maintained by Cory Computer Systems. |

||