By Marina WolfFrom Radiance Summer 2000

I was taken aback. I had never seen so many fat people at once anywhere, much less in bathing suits. They were unabashed and un-ashamed. They took turns sailing gleefully off the diving board.

“I think that what affected me was the emotional part,” says Edell, leaning back in his chair and speaking in that low, no-nonsense voice that has drawn millions of listeners to his radio show on more than two hundred stations nationwide. “It’s easy to say that you know what it’s about. You hear it. You see it. But you don’t really see, or at least I didn’t back then, when there was no—what would you call it?” “Fat liberation?” I suggest tentatively. “Yeah, right, fat liberation movement. That didn’t really exist, except at this swim, and they were very open emotionally. That’s what really did it.” Although fat liberation may have been new to Edell, he was not a stranger to large women and their lives. He had been raised with a fat relative, a young aunt who lived with his family and was raised as his sister. “The battles between her and my mother over dieting . . .” He pauses and lifts his hands, a silent gesture of helplessness in the face of an epic struggle. “I really lived with the pathos and the stress and the strain, and watched what it did to her.” Later Edell again met the fat world when he worked at a chain of weight-loss clinics in Northern California. In his book and in person, Edell is matter-of-fact about what the job entailed: drawing blood for no good reason; giving injections of HCG and B12, again as part of the scam; and prescribing amphetamines for the really stubborn cases. All were standard diet-center practices in the mid-1970s, and obviously, even then, a fraud. But Edell, who had left medical practice to take up jewel smithing and farming in Mendocino County, needed the money for his family. In retrospect, he says, that was one of the best ways to learn about weight. “I had experiences most doctors don’t,” says Edell. “I was essentially working in bariatrics and going through the thousands upon thousands of diets, mostly with women. “I learned, first, that we’re all different. You put people on similar treatments, and you get different results. You learn about the power of the mind in motivating people. You learn how people motivate one another. And you’re involved with the human beings themselves, struggling.” More than twenty years have passed since then. Edell no longer drives a beat-up old car that his patients can hear a half-mile down the road. And he doesn’t give shots anymore. But people are still worrying about weight, more than ever. “It’s probably the number-one health concern Americans have,” he says. “We don’t take all the calls we get on the subject: otherwise, my shows would be dominated by weight and weight issues.”

Edell decries the media’s tendency to pick up on unproven theories and bizarre trends at the expense of the hard-core medical facts that are emerging as researchers train their sights on the long-term medical reality of people living with above-average weights. “The really good studies are coming in now, where they’ve been following people for long periods of time: ten, twenty, thirty years. These studies are starting to tell us, objectively, that you’re not automatically a medical basket case if you’re overweight.” There are some increases in health risks associated with higher weights, says Edell. But he points out that “double the mortality” could simply mean 2 people dying out of 10,000 people rather than 1 person out of 10,000. The risk just isn’t enough to stress out about. “I think that’s an important message for overweight people to hear. They sometimes assume they’re choosing instant death when they stop dieting, and it isn’t true. When you look at the averages, it’s okay. I mean, we all take chances: we drive cars, we do all kinds of things. And this may be just one of those chances that people need to know they can take in life. “When a person is overweight, and they don’t want to spend their lives starving to death or taking pills, they have a right to make that choice, and they have a pretty good chance of living a long and healthy life.” Edell’s opinion is one that seems to be slowly gaining support in the medical community: a subset of people can be “overweight” and not suffer negative health consequences. “It makes sense, because Nature’s not stupid, that those with more of a genetic tendency to be fat can diet, diet, diet, and they just can’t lose weight. But they may do okay with it. With black women, specifically, and older folks, weight seems to matter less. “They’ve also started to find that you can be very fit and also overweight,” continues Edell. “Some studies find that half of overweight people are indeed fit.” These findings come from one of Edell’s favorite sources on fat and fitness, the Cooper Institute for Aerobics in Dallas. Its most famous study found that, in a sampling of 25,000 men, the least fit—regardless of their weight or fat distribution—were twice as likely to die from heart disease. The ramifications of study results like these call for further research, says Edell. “Fitness may come from being active, or it may come genetically. We haven’t quite sorted it all out.” Like most doctors, Edell is careful to suggest that other factors such as diabetes or hypertension may play into whether weight is a problem. But in general, he says, “Dieting may be the unhealthiest thing you can do. The statistics don’t really bear out the idea that we’re getting less healthy as time goes on. We’re going to set a record next year for longevity and heart disease rates continue to plummet.” He leans forward in his chair as his eyebrows shoot up. “That used to be our number one killer. Deaths from heart disease have continued to fall since the late 1960s. So there’s all this ambivalence and doublespeak going on.” At the suggestion that the medical profession is supporting the doublespeak, Edell is typically blunt. “Eh!” he says, waving his hand dismissively. “The medical profession has almost become an innocent bystander in the face of the power of the media. After all, doctors know there’s no magic pill. They know they’re not going to say something to a patient and have them go from 300 pounds to 100 pounds.” It’s societal pressure, Edell says, that drives the medical profession’s involvement in weight-loss endeavors. “How can you sell something to the American public that fails 95 percent of the time? Yet there’s this huge industry out there that continues to do it.” So doctors are essentially powerless, then, to stop the trend? “Yes, doctors are powerless,” he says in a tired voice. “They don’t band together, they don’t have any central authority, they don’t agree on anything. Among doctors are two of the biggest diet gurus going. There’s Dr. Ornish telling you to eat rabbit food and Dr. Atkins telling you to eat pork rinds. They’re both doctors and they’re on opposite ends of the spectrum. So, as M.D.’s, we’re not helping. “We’ll yield to what the public wants. Oh, Doc, you gotta help me diet, you gotta write me a prescription for those pills,” he continues, imitating a patient desperate for a quick fix. “We follow societal trends. If all of a sudden there came a trend to be overweight, then we’d figure out ways to help people with that. Doctors are passive partners.”

Of course, what actually happens at the doctor’s office is something Edell is well aware of. The Maxi Mermaids told him, and he remembers clearly, “You could see in them this fear of going to a doctor.” But some things, he says, just have to be gotten through. Like weighing. “Yes, it is one of those rituals that we do to make you feel, now you’re in a medical setting. But it’s also to establish a baseline, like taking a mammogram when you’re healthy. If you see weight loss that’s not intentional, that’s a very serious sign. If I don’t have a weight to compare to, then my diagnosis is set back for weeks and months. By the opposite token, a sudden weight gain could also have medical reasons. Either way, we need the information. Sometimes,” says Edell, “our embarrassment is dangerous, because we don’t bring up subjects and ask about tests and do things we should.” One thing that patients should do is to get to know a doctor’s biases as best they can. “It’s really important to get a sense of how that doctor feels about you, because that can affect medical judgment,” says Edell. How can we do this: by interviewing a new doctor beforehand? “Yeah, absolutely. Be straightforward,” he says, “Ask, ‘Hey, Doc, how do you feel about fat? Do you think it’s our fault? Should we feel guilty? What do you think about those biases out there in the world?’ Or bring it up indirectly, after the exam. If the doc says, ‘Hey, you’re okay,’ then you say, ‘Not bad for a fat person, huh, Doc? I find that a lot of doctors and other people think if you’re fat, you’ve gotta be unhealthy. What do you think about that?’ “People reveal themselves. We all do. I always tell people to trust their instincts.” However, Edell admits that his own instincts are off in how he uses the terminology of weight. “I know that ‘overweight’ is a judgmental term. I know it and yet I can’t bring myself to use what I’ve been told many times by people in the movement is okay. Getting used to words that we formerly thought were charged, then turn out to be okay with the very people we’re supposed to be sensitive to, is difficult. When I say ‘fat people,’ I still have trouble with it myself, even though I know it’s okay. What about you?” he asks, turning the question around. “What do you say?” “Um, well, I prefer ‘fat,’ but I remember a time when I didn’t prefer it, and it was hard to say.” “See?” he sits back. “Saying ‘overweight’ is like saying ‘overheight.’ That’s something I think about consciously. But when I’m trying to draw people in, sometimes I like to use words that they’re more familiar with to decharge the issue. Or when I’m about to say something radical and challenging, I want to use less challenging, more traditional terminology to sell the idea. But now I know that the word fat is okay.” All this talk about terminology leads Edell to wonder what the clinical word for skinny is. “All my life I was called skinny. As a kid I was uptight about people calling me skinny. My grandmother used to call me Skinny Marink. It’s from a Jimmy Durante song.” He grins a crooked little grin at the moniker that sounds even funnier in his blunt East Coast accent. “So I went through my life wondering, What’s a marink? Is it an animal or something else?” Whatever Jimmy Durante may have meant by “marink,” for the grown-up Edell it’s simply a funny word that makes him smile, even while his TV assistant is yelling out “Ten minutes to makeup!” It’s a flash of playfulness that is as surprising to me as the Maxi Mermaids’ playfulness was to him. It’s a reminder that you can keep a sense of humor—that, indeed, you must—in the middle of shaking up the establishment. ©

MARINA WOLF is a freelance writer living in Northern California. As the Wide-Eyed Gourmet, she has written about food for eleven newspapers across the country. As herself, she writes about herbs, dancing, international travel, religion, size issues, and anything else that strikes her fancy. She can be contacted at fullsun@sonic.net.

Remember,

this is only a taste of what's inside the printed version of the

magazine! |

|

Radiance. |

||

|

This site maintained by Cory Computer Systems. |

||

r.

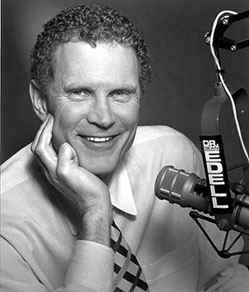

Dean Edell is a self-described “tough nut.” The one-time eye surgeon

has seen a lot of amazing, awful things throughout the course of his

twenty-year career on TV and radio. But Edell’s eyes turn soft as he

remembers the day that he and a camera crew walked into a San Francisco

East Bay aquatic center to do an interview. A significant chunk of the

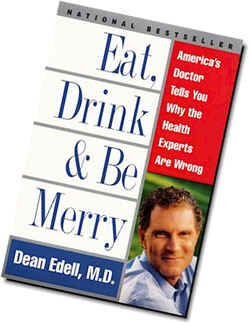

chapter on weight in his book, Eat, Drink, and Be Merry (see

r.

Dean Edell is a self-described “tough nut.” The one-time eye surgeon

has seen a lot of amazing, awful things throughout the course of his

twenty-year career on TV and radio. But Edell’s eyes turn soft as he

remembers the day that he and a camera crew walked into a San Francisco

East Bay aquatic center to do an interview. A significant chunk of the

chapter on weight in his book, Eat, Drink, and Be Merry (see  hen I first picked up Eat, Drink and Be Merry by Dr. Dean

Edell, I was a little distrustful, I admit.

I hate doctors “speaking plain talk.” It’s

usually phoney or condescending. Worse, I always

feel that they leave out crucial bits of

information as they promote their own diets

or vitamin regimens.

hen I first picked up Eat, Drink and Be Merry by Dr. Dean

Edell, I was a little distrustful, I admit.

I hate doctors “speaking plain talk.” It’s

usually phoney or condescending. Worse, I always

feel that they leave out crucial bits of

information as they promote their own diets

or vitamin regimens.