Jodie’s Body:

South African

actress Aviva Jane Carlin reveals

all

on body image, apartheid, and art.

By Elaine Hesse

From Radiance

Summer 2000

hen

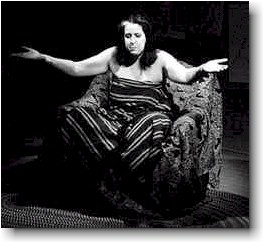

the stage lights come up, a middle-aged woman stretches and strikes a

pose for the implied art students for whom she is modeling. She is naked

as the day she was born. For an hour and fifteen minutes, the character

of Jodie delivers, with compassionate wit, instructions for those who

might consider becoming artist’s models, reflections on the body, and

unbridled joy at the advent of free elections in South Africa. Most of

the time the actress is naked. On stage. Alone. Jodie’s Body was

written by, and stars, Aviva Jane Carlin. An extraordinary play. An

extraordinary woman. hen

the stage lights come up, a middle-aged woman stretches and strikes a

pose for the implied art students for whom she is modeling. She is naked

as the day she was born. For an hour and fifteen minutes, the character

of Jodie delivers, with compassionate wit, instructions for those who

might consider becoming artist’s models, reflections on the body, and

unbridled joy at the advent of free elections in South Africa. Most of

the time the actress is naked. On stage. Alone. Jodie’s Body was

written by, and stars, Aviva Jane Carlin. An extraordinary play. An

extraordinary woman.

Born in South Africa and raised in Kenya,

Carlin later attended London University. A great traveler who has always

attempted to live her political and social ideals wherever she has found

herself, including working for several months in India with Mother

Teresa in homes for the poor, Carlin completed her post graduate degree

at The Drama Studio in London and worked there with the award-winning

Theatre Impact. She moved to the United States in 1989, where she wrote,

taught, and acted. Jodie’s Body is a one-act play which Carlin

wrote and first debuted at a Seattle theater festival in 1994. She has

toured extensively with the play, mainly for women’s groups and

college audiences. By 1998 the show was being staged off-Broadway in New

York as well, where Carlin received strong critical reviews in the New

York Times and the Village Voice.

In Jodie’s Body, Carlin’s

naked body becomes a tool, challenging us to look unflinchingly at the

bare truth of being human.

But Carlin is also asking us to look more

deeply, to see the fear, vulnerability, cruelty, and strength of our

individual and collective existences. She accomplishes this through

Jodie’s remembrances of her childhood in South Africa. As a first-rate

storyteller, she conjures up the art class instructor, George, and

several students; her own mother, “Ma,” a woman with large ideals

and physical girth; her mother’s doctor friend Lally; Jane, her family’s

beloved maid; Jane’s husband, Golden, a long-time employee, now both

physically battered and separated from his wife by the violence of

apartheid; and Toujie, the young daughter of Golden and Jane who is also

Jodie’s childhood playmate.

With her stories, Jodie brings us close

to the profound experiences of terror, courage, and her own accompanying

(childlike) confusion. Without allowing the issues of apartheid and of

conventional ideas of beauty to compete in any forced or inappropriate

way, Carlin manages to put the fight to abolish body size discrimination

and personal shame in powerful, radical perspective.

Never didactic, always captivating, with

her rendering of Jodie as a genuine, earnest character swept up by

memories and emotions three days after South

Africa’s first free election, Carlin’s performance is convincing and

mind-opening.

During an extended theater run of Jodie’s

Body in the fall of 1999 in Sacramento, California, writer Elaine

Hesse talked to Carlin about her work, her life,

and how the two intertwine.

—Catherine Taylor, Radiance

Senior Editor

Hesse: Is Jodie’s Body

autobiographical?

Carlin:

Not strictly. The stories of South Africa come from things that happened

to many people—people in my family or from stories that I would hear

as a child—all woven together. There’s a story about two little

girls who are very, very close friends. One is black and one is white,

and they are pulled apart by the tensions of the country. That actually

happened to my sister, rather than to me. The character of Golden is

based on a real person, but the man who inspired Golden was actually a

farm worker on my grandmother’s farm in South Africa. And there’s

Jane, who is inspired by stories of my mother’s childhood nanny. The

real people never actually knew each other, but in the play they’re

married.

Hesse:

You were born in South Africa, but you weren’t really raised there.

What sort of connection did you feel and do you feel to the

circumstances that you talk about in the play?

Carlin:

I’ve always felt African: East African, South African. Even after

moving from South Africa to Kenya, we went back to visit. Both my

parents have large families there, and they have been there for

generations. We spent time there, and I felt that I understood the

country to some degree. I do have a very passionate attachment to

Uganda, where I mostly grew up. But when Mandela came out of jail, and

with the country’s first free election, I really got in touch with how

South African I felt, how much I cared and how important it was to me.

Hesse:

Where is your citizenship now?

Carlin:

I have South African and British citizenship. Uganda was a British

colony when I was a child there, and at the time of its independence,

the British offered anybody who wanted it a British passport. My parents

immediately said that we were all going to have British passports. My

sisters and brother and I all whined like anything and said that we didn’t

want them, but in those days of emerging Africa, it wasn’t good for a

white person to have a South African passport. So my parents were very

pleased to get British passports for us.

Hesse:

Is your family still in South Africa and Uganda?

Carlin:

My father is in South Africa, my brother is in Seattle, and both my

sisters are in England now. My mother died when I was fifteen.

Hesse:

You’ve traveled quite a bit. What’s been your personal experience of

racism outside of Africa?

Carlin:

For anyone who is raised by South African parents racism is a major,

major, major concern. There’s a line in the play where my character,

Jodie, says, “South Africa is the only thing South African authors can

write about.” And it’s also the only thing they can talk about!

We grew up very aware of the fact that my

parents came from a poisonous society, where anyone who had any

privilege was living on the suffering of other people. It was a strange

and extraordinary way to live. You can’t live passively in South

Africa: in those days of apartheid, if you weren’t doing anything,

then what you were doing was in effect supporting the apartheid

government.

But Uganda—in our little circle that we

moved in anyway—was really quite a haven of racial harmony. The first

really racist remark I heard was when I went to high school in Kenya. I

was thirteen. Although I knew about racism, because my parents talked

about South Africa such a lot, I hadn’t experienced it directly. Kenya

High School had quite strong racist overtones. Not officially; I mean,

none of the staff would put up with it if they heard it, but a lot of

the girls, among themselves, spoke in a very derogatory way about black

Africans. There were four of us from Uganda, all South African, and we

were known as these major liberals in the high school because we refused

to participate in racist remarks and were so adamant and so firm, and

got angry about what we heard.

I found England to be pretty well

integrated, although there’s a vicious strand of racism there as well,

and it shows up in certain sections of the population, and certain

newspapers can be astonishingly racist, right out in the open, in

their headlines. And yet in communities in England where there’s a

mixture of people, it seems to me to work pretty well. But I’m not a

black person living in England; that might be a completely different

experience.

Hesse:

Have you performed Jodie’s Body in southern states of the

United States?

Carlin:

I’ve been to Atlanta and I’ve been to Florida. I really just flew to

Florida, did the show, and flew out again. In Atlanta I stayed a couple

of days and looked around a bit. There was a bit of a kafuffle

during the question-and-answer period after the show. A woman in the

audience—she was a white woman—said, “It’s very interesting to

us, because Americans don’t know anything about struggling and

fighting to get the vote.” There was a sort of ripple of irritation

through the audience, but the woman kept talking, until finally I said,

“Sorry to break in and correct you, but I think you have to say white

Americans don’t know what it’s like to struggle and fight for the

vote, because it’s not very long ago that most of the population

couldn’t vote.” People got quite angry and there was, not a fight

exactly, but a “fierce discussion” among blacks and whites in

the audience. And it was interesting to me, because this was Atlanta!

I mean, for a white person in Atlanta to be unaware of America’s civil

rights struggle seems quite remarkable!

I had my own wake-up call about racism in

the United States in Seattle. I was talking to a black actor—we were

in a show together—and he mentioned very casually that he had been in

jail. I asked (sharp intake of breath), “What did you do? ” And he

said to me, “I didn’t do anything!” And I realized, Gosh, yes, a

young black man in America may well expect to go to jail for nothing.

From my point of view, I assumed that because the justice system worked

reasonably well, if somebody’s in jail they’ve done something. From

his point of view, that was not to be taken for granted at all.

There are two worlds, black and white, and their members perceive things

so radically different because their experiences are so different, even

within the same system.

Hesse:

What made you decide to be naked in your show?

Carlin:

I thought that I would do a show about being comfortable in the body you

live in and also about just enjoying all kinds of bodies. I’d been an

artist’s model, and I moved in a world where every body was valid and

beautiful in its own right.

Gloria Steinem, who was coproducer of the

show in New York, told me how she had started going to baths, women’s

public steam baths. She saw that when everyone had no clothes on, each

body became right in itself. When the clothes went back on, she

could see how the people felt defined by their bodies and how the

culture said “good body,” “bad body.” I found when I was

modeling that as soon as it’s your job to be the object, to be drawn,

then the body takes on its own beauty and power and majesty. You notice

how miraculous and how wonderful the body is. So I thought I would do a

play about the body, and I was going to be quite light and easy.

I didn’t know how to go about it at

first. I mean, if I want to say to people, Consider the possibility of

being comfortable in your body, I have to set that up as a possibility

by being it, and the only possible way I could think of how to be it was

to be naked. Why should people buy it from me if I’m not where there

is risk? I don’t see why people should accept my word for it, unless

[they can see that I am] right on the edge of being uncomfortable. It is

a sort of bad dream we have as children—you’re standing up naked,

completely exposed, and you can’t even cover yourself. There’s a

bright light shining on you and a whole bunch of strangers sitting in

the dark staring at you. I thought, That would be a risky place to be.

So that’s exactly what happens in the theater. There I am: naked,

lights, and strangers in the darkness. I thought that I would take the

risk and be comfortable with it, and have people experience that. People

who are uneasy with nudity have said to me, “Why do you have to do it

naked?” But I can’t say what I want to say without being naked!

Hesse:

What was the first show like? Opening night is generally nerve-wracking

enough when you’re clothed.

Carlin:

What happened was that I came out in the dark, the lights came up, and I

was naked. So the audience’s first view was of the “fat, naked lady.”

And the very first time, the very first moment that the lights came up,

I thought that I would feel self-conscious but that I would get over it

and get on with the play, and I would not be upset with myself if I was

uneasy for the first minute. In fact, what I felt, quite unexpectedly,

was this absolute surge of joy and freedom and happiness, and

there was no doubt in my mind that I had all the power in the room. That

I was, at one and the same time, the most vulnerable and the most

powerful person. I just felt so happy and free and lovely! It passed

across the back of my mind that from now on, I wasn’t going to get

away with saying I couldn’t do things (laughs), because if I could do

this, then there weren’t a lot of things that I’d be able to say I

couldn’t do!

Hesse:

Did you rehearse naked as well? Was it less comfortable to be naked and

mingling with the crew?

Carlin:

That’s the only time there’s a slightly odd moment. Then, and

whenever I do the show at universities and women’s centers. Sometimes

people don’t know. I’ll say, “You need the lights to be

like this, and maybe you’d like to see the flesh so you can get the

tone of the lights.” And they’re like, “What?” And I tell

them I do the show naked, and they say, “Oh, right, yeah, okay,”

and I fling off the robe and there I am, and everybody else has to

adjust. I see my job as just making them as comfortable as they can

possibly be. But it is odd, where we’re talking and working on

something together, it’s very unusual for one person to have no

clothes on in a situation like that. But I must say, it always kind of

amuses me!

Hesse:

You haven’t ever had anyone else decide that they’ll work naked,

too, have you? Hesse:

You haven’t ever had anyone else decide that they’ll work naked,

too, have you?

Carlin:

I did once, at a women’s retreat. At the end of the show, one of the

women took off her clothes. Another one started to, and then got shy,

and then they all closed down. But the first woman was wonderful! She

just ripped off her clothes, stood up with her hands above her head,

turned around, and showed herself to everybody. I thought that they were

all going to jump in and do it, which would’ve been lovely. But

they didn’t.

Hesse:

The show evolves quite a distance, from the theme of being comfortable

with one’s body into issues of apartheid.

Carlin:

The election in South Africa just started writing itself into [the

play]. I can’t say I made any conscious, deliberate decision. I wrote

Jodie’s remark about the fall of apartheid, and it just took off from

there. I think it’s not an uncommon experience for writers; the

writing takes over and starts doing itself.

Hesse:

It seems as if the play is about two very different topics, apartheid

and body image, but in the end these come together in the common theme

of acceptance.

Carlin:

When I was writing, it felt as if I really had two plays. Then it did

sort of come together on its own. I get a little uneasy when people

think that I’m making some comparison between the suffering of fat

women and the suffering of people fighting for freedom in South Africa.

I think that would be a terrible betrayal of the people in South Africa.

I’m sure that people who don’t feel good about their bodies feel

oppressed and feel tyrannized, but you can’t possibly compare that to

living in a tyranny and being oppressed to the point of being tortured.

It’s not the same thing. Sometimes people think that I‘m saying,

Here’s one kind of oppression, and here’s another kind, which disturbs

me. To me the play is saying, Here’s one really, really

important thing, and here’s one thing that isn’t really important at

all!

Hesse:

So rather than drawing a similarity between the two, you’re doing the

opposite: you’re saying to people who are hung up on body image, good

or bad, Get over it. There are a lot more important issues to spend your

energy on! Hesse:

So rather than drawing a similarity between the two, you’re doing the

opposite: you’re saying to people who are hung up on body image, good

or bad, Get over it. There are a lot more important issues to spend your

energy on!

Carlin:

Yeah, that’s part of it. I’m also saying that it ought to be so

easy. If something so powerful and enormous, with the intensity and

brutality of apartheid, can be taken apart, it seems that something that’s

all in our minds should be easier to take apart. Yet women seem to keep

putting themselves through all kinds of misery—which

they could just stop. We could change everything tomorrow if we all just

said, Oh, to hell with it, why should we care anymore? A few businesses

would flounder for a little bit, but on the whole, life would be easier!

Hesse:

Do you get mail from people who have been to the show?

Carlin:

Not often, no. People come and speak to me after the show. Or if people

see me on the street, they always come and speak to me. Everyone is very

warm and friendly.

Hesse:

Do you sense that people feel close to you because they’ve spent time

with you while you were naked?

Carlin:

Yeah, they do. People feel that they know me really well, and they tell

me things. They’re just so open about their own feelings. People—total

strangers to me—just walk up and put their arms around me and feel as

if there’s nothing odd about it at all. And I find it lovely that’s

what we’ve created together in the space of an hour and fifteen

minutes. That we’ve made intimacy among strangers and that people feel

love for someone they knew nothing about an hour earlier is very

wonderful, very sweet. People will tell me, “When the show started, I

just thought that you looked so gross, so disgusting, and by the end of

the show, I just thought that you looked so beautiful!” And I think,

Well, they must really feel comfortable with me to be able to tell me

something like that.

Hesse:

I didn’t find your being naked distracting at all, after the initial

novelty wore off. It is pretty rare to see someone, of any body type,

completely naked on stage for such a long time, but in this case, it’s

in context, and the nudity becomes, in a sense, the costume.

Carlin:

I’ve had that comment before, that my nudity becomes the costume that

my character is wearing. Jodie is an artist’s model, and nudity is

integral to what she’s doing. You were talking about the novelty of

it, and how you don’t see many naked bodies performing on stage or

anywhere else. Well, I think that we all secretly wish that we could see

more. I think we all would love to look at one another, in one of these

open changing rooms at the swimming pool or somewhere, but it’s so not

okay. We carefully avert our eyes and make sure that everyone

understands that we’re not staring. And yet I think there’s a sort

of yearning in us to see one another naked. It’s partly just interest—not

a prurient interest, necessarily—but a natural sort of interest in the

human body, because every person has one and lives in one. I think that

it’s quite a lack in our society that we’re not able to look, and

that’s part of what I want to give. I say to people, This is what you’re

supposed to do. You’re supposed to sit, be comfortable, and gaze and

gaze at somebody else’s naked body, and nobody is going to stop you or

think anything bad of you for it. You can look wherever you like, for as

long as you like. And you can listen or not listen: you’re the

observer. I think people like it.

Hesse:

Do you think the United States is especially uptight about nudity?

Carlin:

I think that this country still has a very strong puritan streak. I hadn’t

been in America that long when I started telling people about the show

and how I was going to do it naked. That seemed to be really startling

to people. I had a European sensibility about it, and I didn’t think

that it would be particularly surprising. Friends of mine in Europe didn’t

think so. The United States is just a different culture, one that is

still a little held back, but in the end I decided to go ahead.

Hesse:

What next for you?

Carlin:

A new play commissioned by the Public Theater in New York, on the

strength of Jodie’s Body. I hope that they will produce it. It

comes out of the time I spent in India working for Mother Teresa in the

Homes for the Poor project in Calcutta.

It’s like Jodie’s Body in that

experiences are woven together. But there are nine characters in it, so

it’s much, much bigger than Jodie’s Body, and it has more of

a real story.

Hesse:

Will you perform it as well?

Carlin:

Oh yeah. I write only so that I can act. Acting is absolutely my top

thing.

Hesse:

Will you continue to tour with Jodie’s Body?

Carlin:

Yes. I have performances scheduled, mostly at colleges and women’s

conferences.

Hesse:

I haven’t asked about your personal life. Are you married, single?

Carlin:

I’m with somebody, not married, but in love. He’s a South African.

He’s in New York. He came to see the show and he loved it. All my

friends made the obvious comment: “Well, he’s seen you naked, so at

least that hurdle’s over with!” He called and asked me out. That’s

how we got together. He’s a performer and a writer. He’s wonderful.

He’s a very, very brilliant man.

It’s funny because I used to say when I

was a child that I wanted to marry a South African. And here I am,

nearly fifty, and at last the South African has appeared!

Hesse:

Do any stories come to mind about a particular performance or audience? Hesse:

Do any stories come to mind about a particular performance or audience?

Carlin:

Mmm . . . Rather a sad one, actually. It was in North Carolina, I think.

There was someone whispering way up in the back of the audience as I was

performing. It went on for a bit, you know, and I just sort of

carried on. Then there was a sort of a scuffle, and somebody was

obviously leaving. I thought somebody had been feeling ill and had to

go. After the show I stayed to answer questions from the audience. One

of the people at the back apologized to me for the person “who had

been saying those terrible things.” So I said, “Oh! What terrible

things?” Then the person realized that I hadn’t heard and just said,

“Never mind.” But I was terribly curious, so I asked

afterwards, and apparently a young man in the costume department had

been sitting there, just letting forth a stream of invective

about how disgusting I was. He was really, really

upset, and kept it up until the people around him finally said, “Shut

up or leave.” He just couldn’t handle it at all. He was

calling me a pig, and things like this, really, really an

upset person. The audience thought that I could hear him, which, of

course, upset them dreadfully.

Hesse:

And he was from the costume department?

Carlin:

Yeah, when I found that out, it seemed almost a joke, as

if maybe he was saying, Why do I have to sit through a play without any

costumes?!

Hesse:

I guess that it’s good to warn everyone about the nudity, then, in

order to prevent such a situation. But I can’t help feeling that all

of the press focusing on the “naked lady” somehow cheats the public

out of knowing what the play is about before they decide whether to buy

tickets.

Carlin:

I feel that. I wish that people wouldn’t make the nudity such a huge,

major feature. I guess people think that it’s going to sell the paper

or that it’s going to draw people to come and see the play. But as it

goes on, I get more and more fed up with it. I would really like to see

a headline that just says, South African Play Celebrates the Fall of

Apartheid, without a single word about anyone being naked. ©

After twelve years as a Sacramento

radio broadcaster, ELAINE HESSE has found her niche as a freelance

writer and reporter. She lives in Sacramento with husband Bob, son Ryan

(four years old), and Ryan’s six imaginary dinosaur friends (all

girls). This is her first nationally published magazine article.

Remember,

this is only a taste of what's inside the printed version of the

magazine!

|